On the Frontier

Fort Union appealed to my interest in the fur trade and frontier. This famous trading post is right on the border between Montana and North Dakota. The fort is in North Dakota, but the parking lot is in Montana, not that the parking lot was much good to me.

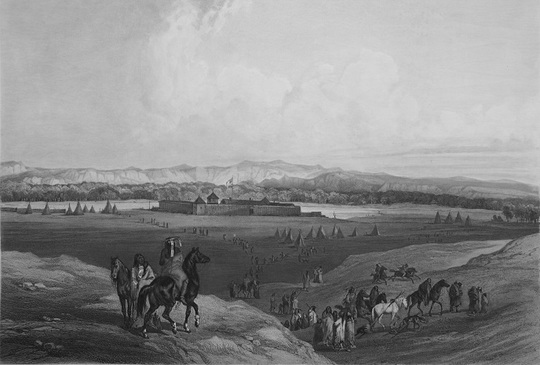

Built in 1828, Fort Union has a long and coloured history and was a trading hub in the beaver pelt and early buffalo robe trade. The fort’s construction and operation were backed by John Jacob Astor, a wealthy fur merchant and businessman with varied financial interests who would become America’s first millionaire, and, when his fortune is adjusted for inflation, the fourth richest American of all-time.

Astor’s involvement in the fur trade was through his American Fur Trading Company. His business was simple – exchange manufactured goods with Natives for the luxuriant pelts they hunted and trapped. Customers were of many different First Nations including the Lakota Sioux, Hidatsa, Blackfoot, Ojibwa, Cree, Crow and Assiniboine. The Metis also shopped here. In exchange for beaver, buffalo, fox, badger and other furs, the customers sought wool blankets, beads, alcohol, knives and axes, cookware, tea, paints and other items that they didn’t make themselves.

I could imagine the excitement the customers must have felt when arriving at the fort. I certainly felt it. After spending a winter trapping furs, which is when they are at their thickest and most valuable, the Indian and Metis had travelled during the spring and early summer for weeks, maybe even a month or more, to trade at the fort. They would have looked forward to seeing their friends and relatives. I’m sure they had visualized what they would buy and probably felt the same awe and wonder we feel when looking at a catalogue and longing for a special item. Maybe it was a new muzzleloader or beads to decorate their clothes.

I arrived as many of them would have – by water. The fort’s huge flag was visible for miles and served to help locate the structure behind the tall stand of cottonwoods which obstruct the wooden palisade and the white stone bastions. I secured my canoe to shore and imagined I heaved a bundle of beaver pelts over my shoulder. Would I remember everything? “Don’t forget the gunpowder, coffee, sugar, traps, snare wire and a four-point wool blanket.”

Walking through the main gates, I realized there was a cannon pointing at me from the middle of the court yard, a clear message to thieves. Dressed in a period costume, an interpreter greeted me and he showed me the selection of goods. The colours of the blankets and beads were captivating, hypnotic. After spending two months outdoors, I was used to seeing the greens, browns and blues of vegetation, earth, sky and water. The vibrant yellows, reds and purples aren’t as common and attracted my eye.

The tour guide explained to me that trading was a spectacle, an event. The Natives would watch their best negotiators take on the fort’s best negotiators. Because the Aboriginals and traders hadn’t seen each other in several months, the customers were received in what was called the Indian Room where the fort staff would serve food and exchange news and happenings from the past winter. This ceremony would last for hours and cement the relationship between the trader and his guests.

I didn’t have time to camp at Fort Union, but if it were 150 years ago I would have spent a few weeks in the area visiting with my friends and relatives as they came to trade.

I walked through the cottonwoods and willows to the water's edge and pointed my canoe towards Lake Sakakawea (Sa-kaka-way-a), the first of five huge reservoirs that were created when the Missouri River was dammed at intervals. Lake Sakakawea is 180 miles long and would test the strength of my determination.

Built in 1828, Fort Union has a long and coloured history and was a trading hub in the beaver pelt and early buffalo robe trade. The fort’s construction and operation were backed by John Jacob Astor, a wealthy fur merchant and businessman with varied financial interests who would become America’s first millionaire, and, when his fortune is adjusted for inflation, the fourth richest American of all-time.

Astor’s involvement in the fur trade was through his American Fur Trading Company. His business was simple – exchange manufactured goods with Natives for the luxuriant pelts they hunted and trapped. Customers were of many different First Nations including the Lakota Sioux, Hidatsa, Blackfoot, Ojibwa, Cree, Crow and Assiniboine. The Metis also shopped here. In exchange for beaver, buffalo, fox, badger and other furs, the customers sought wool blankets, beads, alcohol, knives and axes, cookware, tea, paints and other items that they didn’t make themselves.

I could imagine the excitement the customers must have felt when arriving at the fort. I certainly felt it. After spending a winter trapping furs, which is when they are at their thickest and most valuable, the Indian and Metis had travelled during the spring and early summer for weeks, maybe even a month or more, to trade at the fort. They would have looked forward to seeing their friends and relatives. I’m sure they had visualized what they would buy and probably felt the same awe and wonder we feel when looking at a catalogue and longing for a special item. Maybe it was a new muzzleloader or beads to decorate their clothes.

I arrived as many of them would have – by water. The fort’s huge flag was visible for miles and served to help locate the structure behind the tall stand of cottonwoods which obstruct the wooden palisade and the white stone bastions. I secured my canoe to shore and imagined I heaved a bundle of beaver pelts over my shoulder. Would I remember everything? “Don’t forget the gunpowder, coffee, sugar, traps, snare wire and a four-point wool blanket.”

Walking through the main gates, I realized there was a cannon pointing at me from the middle of the court yard, a clear message to thieves. Dressed in a period costume, an interpreter greeted me and he showed me the selection of goods. The colours of the blankets and beads were captivating, hypnotic. After spending two months outdoors, I was used to seeing the greens, browns and blues of vegetation, earth, sky and water. The vibrant yellows, reds and purples aren’t as common and attracted my eye.

The tour guide explained to me that trading was a spectacle, an event. The Natives would watch their best negotiators take on the fort’s best negotiators. Because the Aboriginals and traders hadn’t seen each other in several months, the customers were received in what was called the Indian Room where the fort staff would serve food and exchange news and happenings from the past winter. This ceremony would last for hours and cement the relationship between the trader and his guests.

I didn’t have time to camp at Fort Union, but if it were 150 years ago I would have spent a few weeks in the area visiting with my friends and relatives as they came to trade.

I walked through the cottonwoods and willows to the water's edge and pointed my canoe towards Lake Sakakawea (Sa-kaka-way-a), the first of five huge reservoirs that were created when the Missouri River was dammed at intervals. Lake Sakakawea is 180 miles long and would test the strength of my determination.